We are family

This article by Bruce Munro was originally published on odt.co.nz on 7 July 2024.

Anti-clockwise from above: Dunedin mayor Richard Walls (left) and Shanghai Mayor Huang Ju sign the Dunedin-Shanghai sister city agreement, October 21, 1994. The Yu Yuan, in Shanghai, has only one sister garden in the world, the Lan Yuan, in Dunedin. Deputy director-general Liang Ye (standing) with fellow members of the Shanghai Foreign Affairs Office and representatives of the Chinese Peoples’ Institute for Foreign Affairs. Shanghai skyline, June 2024. Dunedin mayor Peter Chin signs the Yu Yuan and Lan Yuan sister gardens agreement, watched by New Zealand and Shanghai dignitaries including Trade Minister Phil Goff (back, third from left), in Shanghai, in November 2006. Photos: Bruce Munro/ODT files

The Dunedin-Shanghai sister-city relationship turns 30 this year. Why does one of the world’s largest municipalities have special affection for our small city? And what is the future of this relationship, rated a gold-standard sister-city bond?

Bruce Munro travels to Shanghai, and talks to former Dunedin mayor Peter Chin, to find out.

A light drizzle softens the 35°C lunchtime swelter on the front steps of 1418 West Nanjing Rd, central Shanghai.

Less than 5km east is The Bund’s colonial era, luxury-brand stores, which glower across the Huangpu river at ultra-modern, skyscraping Pudong. But here, in a leafy low-rise oasis near the Portman Ritz-Carlton hotel, are the gracious columns and balustrades of the 1926 Guo Brothers building, home to the Shanghai Foreign Affairs Office (FAO).

A mere three storeys tall, the Shanghai FAO is the prefrontal cortex of Shanghai Municipal Government’s worldwide network of 94 sister cities (not to mention 98 second-tier “friendly exchange relationships”) that include London, San Francisco, Mumbai, Dubai, Istanbul, St Petersburg – and Dunedin. It is from here the global engagement priorities and plans of one of the world’s major centres of finance, business, research and technology are set in motion.

And second in charge of the 26-million-person metropolis’ external affairs office is Liang Ye.

Deputy director-general Ye has just given us more than an hour of her time, answering questions about the past and present, laying out ideas for the future of Shanghai’s 30-year relationship with its 129,000-person antipodean sister city.

Seeing us out to our transport, Ye has a question of her own.

“Do you know former Dunedin mayor, Peter Chin?

“Please pass on my warm greetings to him.”

Thirty years ago this October, the mayors of Shanghai and Dunedin, Huang Ju and Richard Walls, signed a formal sister-city agreement, pledging their towns to the pursuit of familial friendship, understanding and co-operation.

The origins of the sister-city relationship, as is common with creation accounts, has more than one version. In Shanghai, records show Dunedin made the first approach, to which Shanghai gave the culturally appropriate response – “When someone extends a friendly gesture to establish friendship with us, we are ready to respond with the same positivity,” Ye says.

Dunedin City Council archives record Mayor Walls taking a call from the Chinese embassy in New Zealand asking whether the city would be interested in a sister-city relationship with Shanghai – “Reportedly the Dunedin Mayor was flattered but puzzled … His unequivocal response was, ‘Absolutely’,” Enterprise Dunedin manager John Christie says.

A delegation from Shanghai came to Dunedin for the formal signing, inked on October 21, 1994.

A couple of months later the Dunedin Shanghai Association was set up to aid connections and exchanges.

Sukhi Turner became Dunedin mayor in late 1995. Her concerns about China’s human-rights record meant she only visited Shanghai in an unofficial capacity during her three-term mayoralty. The Otago Chamber of Commerce, however, maintained links, Mr Christie, who was then the chamber’s chief executive (and has visited Shanghai more than 50 times during the past three decades), says.

Official city-to-city interaction increased again under successive mayors, beginning with Peter Chin, who took the top seat in late 2004.

Chin, now retired and living in Roslyn, says the centrepiece of that growing Dunedin-Shanghai relationship has been Lan Yuan, Dunedin’s Chinese Garden.

A Dunedin-born lawyer, Chin had become a city councillor in 1995. Two years later, he was also made chairman of the Dunedin Chinese Garden Trust, set up by Otago Chinese to explore gifting a garden to Dunedin to mark the city’s 1998 sesquicentennial.

“Everybody thought it was a bloody good idea,” he says with a chuckle.

“But bearing in mind, we were mostly first generation New Zealand-born Chinese who really didn’t have too much an idea of what the hell it was we were wanting to build.”

An architect was engaged and the site next to Toitū Settlers Museum was chosen. The garden was still not much more than a concept when Shanghai’s deputy mayor and entourage – here for the opening of an exhibition of Shanghai Museum bronzes at Dunedin Public Art Gallery – also attended the garden’s foundation-stone laying ceremony in March 1998.

The day after the exhibition opening, Chin took the Shanghai museum curator to watch the Highlanders play rugby at Carisbrook Stadium.

Neither spoke the other’s language, but by the end of the game the curator, a distinguished professor, was “roaring with everyone else”.

“We became great friends,” Chin says.

The Shanghai delegation got to know about the proposed garden. But more importantly, Chin says, they got to know the history of Chinese migrants in New Zealand. Taken by historian Dr James Ng to visit gold mining sites in Central Otago, the Shanghai officials heard about the persecution, the poll tax, the difficulties Chinese faced here.

The impact can be measured by their response.

“They basically said, ‘You’re building a garden to give to the city, after the ways you’ve been treated over the years; we admire what you are doing and we would like to help you build the garden. We will do it for you’.”

Over the next several years, Shanghai provided much of the expertise, material and manpower to do just that.

Dunedin’s garden, Lan Yuan, was modelled on gardens such as Yu Yuan, a renowned classical garden in Shanghai’s old city. Lan Yuan was built in Shanghai, taken apart, transported to Dunedin and then rebuilt onsite by 50 Chinese tradesmen.

The trust still needed to fundraise the $7 million cost. That was helped by a $3.7 million grant from the New Zealand government, which was desperate to clinch the world’s first Free Trade Agreement with China, and by the Shanghai government sticking to a fixed construction price, despite cost blowouts.

The only authentic Chinese garden in the southern hemisphere, and one of only three outside China, Lan Yuan was officially opened in September 2008, the same month the sister-city relationship was renewed.

“There were a whole lot of things they bit the bullet over because the garden was something they wanted to happen. The goodwill between the two [cities] was huge,” Chin says.

In March 2010, Lan Yuan signed a sister garden agreement with Yu Yuan, becoming its first and only “sister”.

“Shanghai always looked at the Dunedin sister-city relationship as one of their top-three strongest sister city links.

“They’ve said the office of the Mayor of Shanghai is always open to the mayor of Dunedin and the prime minister of New Zealand. That relationship to them was hugely important. Why? I don’t know.”

Walking the thronging streets of Shanghai, the answer is hard to find.

This, in a city where it is possible to find anything and anybody at any hour.

Yes, it is the second city of a powerful, one-party state, where crossing the street against the lights can see you sent a fine, courtesy of myriad facial recognition-enabled surveillance cameras. But it is definitely “communism with Chinese characteristics”, chief among which seems to be concessions to the spirit of commerce.

A few kilometres east of the Shanghai Foreign Affairs Office, Nanjing Rd becomes a broad pedestrian avenue lined on both sides by a prized collection of China and the world’s foremost retail stores, all holding continuous sales. In the early evening, Shanghainese locals and tourists in their many thousands stroll and shop their way down this vibrant, billboard-lit, consumer canyon.

Shanghai is easily China’s most cosmopolitan city. Mandarin predominates, but languages from all continents are heard, especially Japanese, French and Korean.

And Shanghai, like China as a whole, is going places – fast. In the past three decades, the number of people in China living below the poverty line has dropped from more than 60 million to less than 1.6 million. In the past 10 years, the disposable income of the typical Shanghai resident has almost doubled.

To do this, the country has embraced technology. Nobody carries cash on Nanjing Rd’s pedestrian street; all the retailers, from the No 1 Department Store and Tiffany’s to the moon cake stall in the Shanghai First Food Hall, prefer Alipay or WeChat’s QR code-based, mobile payment platforms. And where Nanjing Rd again permits vehicles for its final 1.5km stretch to The Bund, a third of the cars and two-thirds of the buses are electric.

Across the river from The Bund, Pudong has been transformed in 30 years from a shipyard to a parade of haute-couture skyscrapers.

South of there, where the waters of the Huangpu river, mixed with those of the Yangtze river, flow into the East China Sea, Shanghai’s container port – the busiest in the world – continues to fuel the city’s seemingly unstoppable growth.

Why, indeed, would Shanghai so value its sister-city relationship with Dunedin?

The answer comes during the hour spent across a large wooden boardroom table from Ye.

In a high-ceiling room with a marble fireplace, ornate wood panelling and doors adorned with leadlight scenes from nature, the deputy director-general – mostly through an interpreter, but also in her own competent English – answers questions about the history, nature and substance of the two city sorority.

“I think the co-operation is delicate, small-scale but very nice,” Ye says, adding later that the relationship itself is “dynamic, sound and robust”.

She talks about this year’s 30th anniversary; mentioning trade talks as well as civic, business and educational exchanges that will include a visit to Shanghai by Dunedin Mayor Jules Radich, the date of which is yet to be confirmed by Dunedin.

“This [mayoral] visit should be a highlight among all our celebration events in commemoration of the 30th anniversary.”

Asked about the future, Ye expresses the view that it is time for the relationship to move beyond a focus on people-to-people exchanges.

“We believe it is necessary for us to further boost the co-operation ties … so we can better serve the socioeconomic development of our two cities.”

Specifically, she mentions the green economy, digital economy and tourism as areas of interest Shanghai would like to explore.

“Probably we can request our two city leaders to sign MOUs to lay a more solid foundation for the future co-operation between our two cities.”

Back in Dunedin, Christie will later detail the city’s ongoing Shanghai-focused education, research and economic development work, as well as confirming Dunedin’s interest in the areas outlined by Ye.

“Digital is probably the area we’ve got our focus on more; though not to say we wouldn’t also on green [economy],” Christie says.

A spin-off project from the Centre of Digital Excellence is already being looked at.

“It’s what we call games for health, or serious games; looking at health technologies and digital interactive health.

“We’re very keen to see what’s happening in that digital health space in Shanghai.”

The answer to the Shanghai “why” starts to unfurl when Ye talks about her city at the time when the sister-city relationship with Dunedin was first being explored.

“At the beginning of the 1990s, the Pudong area was just starting a new round of reform and opening up. So, Shanghai at that time was not as developed as what we see now.”

It was not then a global city; it was smaller, less confident, still on its way up.

Her statement triggers the memory of an off-the-record comment made a few days earlier by a well-placed person who believed Shanghai felt a debt of gratitude to Dunedin.

It seems at odds with Peter Chin’s recollection of the power dynamics when, as mayor, he first hosted a Shanghai delegation in Dunedin.

“It was bloody scary. They had all the money, they had all the power, they knew what they wanted. We didn’t know what we wanted … We were novices, but they were just so, so patient.”

But it is confirmed 15 minutes later when the question is put to Ye: “What benefits does Shanghai, or China, get from the sister city relationship with Dunedin?”.

“Before I answer this question, I would like to remind you that Shanghai was not prosperous from the start,” she says.

“I still remember, when I was a little girl, we used textile bags to do shopping; plastic bags were luxury items. At that time, New Zealand was, and still is, a developed economy.

“We learnt a lot of cutting-edge technologies, we gained a lot of new ideas and interesting initiatives from New Zealand.

“And throughout our process of co-operation and exchange, we feel an equality. Dunedin didn’t look down on Shanghai or China because of your advanced economic status. It was this kind of equality and equity that actually made the co-operation benefit both sides of this equation.

“So, however much Shanghai will develop, we will always stick to the same value of equality.”

Another piece to the puzzle

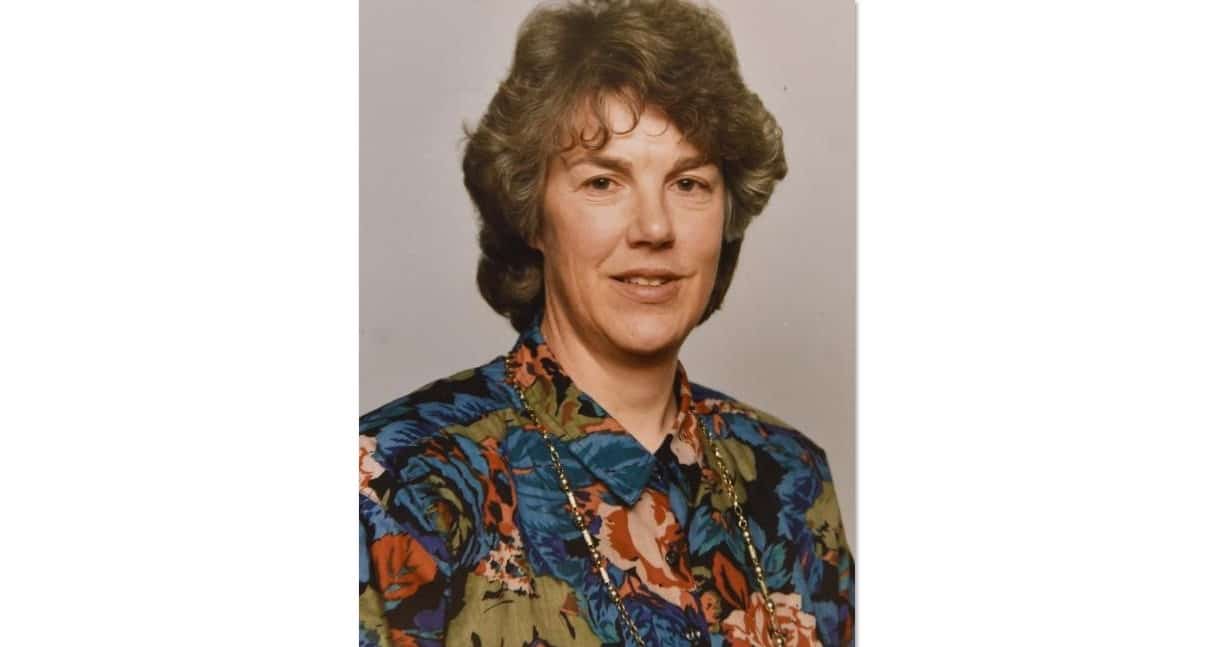

Louise Croot, pictured here in 1991, says the Chinese embassy first suggested a sister city relationship between Shanghai and Otago Regional Council. PHOTO: ODT FILES

LOUISE Croot, 82, MNZM, has added another piece to the puzzle of the origin of Dunedin’s sister city relationship with Shanghai.

Croot, who was an Otago Regional Council councillor for 27 years from 1990 to 2016, says she was approached by the Chinese embassy with a sister city proposal in 1993.

The year before the Dunedin-Shanghai sister city relationship was formalised, Croot says she was at a New Zealand China Society meeting when the cultural attaché from the embassy made the offer.

‘‘The person asked if I could approach the Otago Regional Council to be the sister city link for Shanghai,’’ Croot recalls.

After thinking about it and talking with others, she concluded it would be more appropriate for Dunedin to forge the relationship.

‘‘I went to meet [Dunedin mayor] Richard Walls and he said he would contact the embassy as requested.

‘‘He felt it was a challenge and a bit of a ‘David and Goliath’ situation.

‘‘ I always appreciated Richard’s initiative.’’

Also involved were Dunedin City Council (DCC) economic development manager Paul Crack and historian Dr James Ng – ‘‘who had been consulted as it was not the geographic area most of our local Chinese families came from’’.

‘‘I was present, with my late husband Charles Croot, at the first memorandum of understanding signing, at Larnach Castle.’’

Croot maintained links for some time, helping to set up the Dunedin Shanghai Association.

MENU

MENU